Wer im Schatten bleibt,

der stirbt

Death in the Shadows

by Andreas Platthaus

At the beginning of 2011, everything appeared to be going well, both with the project and the financing. Things were progressing quickly, and, upon first glance, “Black.Light” looked even better than one could have expected a year ago. But now there’s money trouble, even though 10 leading illustrators are currently working on “Black.Light.” It’s so typical: Initially, leading artists and journalists are quick to show an interest for the desperation in the world’s nether regions. They develop a concept to bring together not only the most disparate forms of storytelling, but also people from north and south, from wealth and poverty, from light and shadow. Then, out of nowhere, the genesis of something spectacular suddenly draws the focus of attention and the financial means to something much more appealing, because we prefer to document beauty instead of ugliness, to show that which puts us in a good light instead of what our shadows are. Now, there is no more interest in “Black.Light” because that something spectacular is last year’s Arab Spring. But what does it have to do with Black.Light?

First, one has to ask: What is Black.Light? Simply posing the question speaks volumes about the problems of the project. Normally, one would think a cross-border and cross-discipline concept for presenting human tragedy through a combination of artistic and documentary styles would stir interest and attract support. But during the time in which the tragedy played out – 1989 to 2007 – it was given short shrift outside of Africa. Fighting in the successor states of Yugoslavia, the Middle East conflict and two Iraq wars were more than just competition for publishing space: They made the West blind to the horrors in regions that are merely on the periphery of its spheres of interest. So much is true for areas like West Africa. From 1989 to 2007, Charles Taylor defined life in that part of the world. The Liberian warlord carried the power struggle for his homeland to neighboring states before actually becoming president of Liberia following the 1997 civil war. Once in office, he fomented a second civil war and further international conflicts. International pressure forced his resignation in 2003, he was extradited from his exile in Nigeria in 2006, and in 2007 he found himself charged with war crimes in Sierra Leone by a U.N. Special Court in The Hague. The trial against the man who once set West Africa aflame in still underway. Black.Light tells the story of the effects of Taylor’s actions.

With interest in these events having been so little, nearly everything Black.Light portrays is new to us. It reveals a part of the world irradiated by a black light, one only illuminating individual details in a bizarre way. And there was always death in the shadows. During these times, German photographer Wolf Böwig and Portuguese reporter Pedro Rosa Mendes travelled repeatedly to the four West African states of Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea–Bissau and Ivory Coast. They returned with award-winning reports which were published around the world. Böwig and Mendes were even nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in 2007. As the photographer put it, “Pedro writes what I see, and I seem to photograph what interests him.” But that wasn’t enough for them. Why not try to explain things so many people don’t want to know in a manner that attracts more interest and reaches the people of Africa? A few years ago, when Mendes was a juror for Lettre International’s Ulysses Award, he was looking over submitted work and asked offhandedly, “Why aren’t there any illustrated reports on the table?” The question remained unanswered, but it provided a challenge, one that also inspired Böwig.

The two men sought out others to help raise the flag, and in Böwig’s hometown of Hanover they found graphic designer Henning Ahlers and designer Christoph Ermisch. Together, the four of them developed the concept behind Black.Light: Mendes and Böwig’s reports were provided to illustrators who drew stories based on their bedrock. To call the results “comics” is not enough: the style allows for illustrations placed alongside Mendes‘ prose and Böwig’s photographs.

It is a hybrid style, one that until now was only known in France. From 2003 to 2006, comic artist Emmanuelle Guibert and colorist Frédéric Lemercier created three volumes based on a trip taken by French photojournalist Didier Lefèvre, who travelled with the charity Doctors Without Borders to Soviet-occupied Afghanistan in 1986 and documented the journey with numerous photos. The trilogy, called “The Photographer” (First Second, 2009), was also much more than a comic book. The series combines the respective strengths of written and photographed memories with those interpreted and illustrated by the hand of another. Photographs run alongside comic panels enriched with descriptions and speech bubbles – and in each case, these testimonials compliment what is missing from the other forms of documentation.

This is exactly what Black.Light aspires to, except instead of having merely one illustrator produce graphic interpretations from a report of word and pictures, there are many. Through this method, the uniform “signature” of Mendes’s stories and Böwig’s black-and-white photographs is supplemented by the work of other artists. However, this is not only an observation from the outside. A constant component of Black.Light’s working principle is the role of public workshops where, more than anything, leading West African newspapers should also be involved. (as well as those people whose stories Mendes and Böwig tell with their reports). Thus, the illustrators can envision their own points of view and their explanations of the events.

This model orients itself on South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which has become a proven method throughout the African continent for coming to terms with political crimes – especially in Sierra Leone. The results of these workshops are to not only form the foundation of the book, but also to travel the world as an exhibition, above all, to West Africa. One workshop is being conceived for Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, together with an open-air presentation of the illustrated stories. This will increase the intensity of the cardinal question: How well does the predominately oral storytelling tradition of this region blend with the Western style, which fixates on words or pictures? And what about the problem of illiteracy? The oft-touted universal accessibility of picture stories will need to prove itself.

Following through with such a plan requires money. In the beginning, this did not appear to be a problem. “Various foundations made wholehearted promises to us, none of which were kept by any of the institutions,” Ahlers recalls. With the onset of democratic movements in North Africa, the region south of the Sahara once again became what Black.Light is fighting against: A blind spot in public perception. Western institutions quickly targeted their efforts at states with democratic movements. There wasn’t a festival which didn’t hastily integrate art and artists from the Maghreb, and there wasn’t a foundation that didn’t get wind of how effective their engagement would be for public relations. Black Africa? It would have to wait, yet again.

Of course, Böwig and Ahlers, the protagonists behind Black.Light, couldn’t have foreseen the outbreak of the so-called “Arabellion” when they presented their proposal at the 2010 Frankfurt Book Fair. In tow, they carried the first “dummy,” an initial layout, to show how they wanted to portray the wars in West Africa with a combination of text, photographs and illustrations. A lot of effort went into this preparation, as did a considerable amount of money.

Things ratcheted up a year later when Böwig and Ahlers met with Emmerich at his Hanover office to view the progress. The men see themselves indebted to the three illustrators who have been working on Black.Light just so the initiators have something to present. Artists who have been contacted about the project have shown a strong willingness to participate. Ten have already committed, including Paris-based comic legend Lorenzo Mattotti and the famous American superhero illustrators George Pratt and Greg Ruth. Nic Klein, one of the few Germans to establish himself in the American comic book business, and Cambodian-born French artists Séra and Benjamin Flaó will also be involved. Earlier this year, Italian illustrator Stefan Ricci, one of the most accomplished and unorthodox contemporary graphic storytellers, accepted an invitation.

None of these artists, all of whom are doing well professionally, expect to be paid standard rates for Black.Light. But they shouldn’t have to work for free, either. “If we don’t find any sponsors, we will pay three of the illustrators,” Böwig says. On the other hand, things are looking up in at least one aspect: The Berlin-based Avant Verlag, a small but well-respected comic book publisher, has agreed to add the book to its program. And the first workshop is scheduled for the beginning of June in Erlangen, Germany, as a prelude to the International Comic Salon (June 7 to 10), which will feature a presentation of the Black.Light project. Things are gearing up, even without any financial security.

Various African guests are expected at the Erlangen workshop, where Böwig and Mendes will sound the starting gun for Black.Light. The project is no longer a simulation; illustrators have two months to finish their stories, and the results will be presented as an exhibition in October in Hanover. Ahlers has additional expectations. “The illustrators are to travel, not only to Erlangen, but also into the unknown.”

Visitors will definitely have something to see at the Comic Salon, with three test stories from the projected pool of 15 to 18 reports to be illustrated already complete. This is why Ermisch has cleared the long work table in his office. A strip on the wall holds up lengthy columns of printouts fastened together, enabling him to scrutinize the arrangement of image sequences. Illustrators won’t have the last word about how the laid-out stories in the extra-wide book format will appear. Ermisch takes the delivered illustrations as raw material for the layout. He cuts, enlarges details and occasionally arranges them with photos. The result will look more different than any of the illustrators might dare to imagine. “Everyone has to be ready to expose themselves,” according to Böwig. This is part of the allure.

Böwig learned this when he won Danijel Zezelj for the project in New York in 2010. Zezelj, who was born in Zagreb, works for a number of American comic book publishers. As a painter, he has had an exhibition on show at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. To make the concept plausible, Böwig took individual images from one of Zezelj’s “Captain America” comics and combined them out of their context with Mendes’s words. After the delivery of this somewhat audacious demonstration, an enthusiastic ?e?elj called a mere two hours later to commit to the project. In the end, it was the liberal use of his images which convinced the artist. He disappeared for 10 days to immediately start converting one of the reports into pictures.

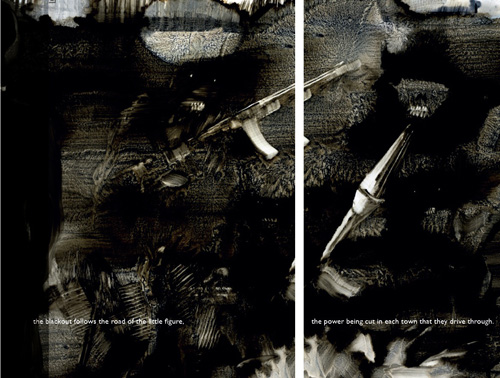

Another person inspired to begin work immediately was Belgian-born illustrator Thierry van Hasselt, one of the most important proponents of avant-garde illustrated stories in the French-speaking world and co-founder of Frémok Publishing. He selected one of Mendes’s more unconventional reports: An allegory about Charles Taylor. Entitled “Black Sun”, it takes place in Ivory Coast and tells about the arrival of a nameless warlord at an airstrip in a remote province from which a convoy of vehicles embarks for a distant destination, always under the cover of night as accomplices cut the electrical service to each town the convoy passes through along the way.

Van Hasselt is the perfect choice to illustrate this “bulimic celestial body” – Mendes’s description of a warlord who creates only darkness around him. Wild, thick brushstrokes cross double pages, which unfold to a width of nearly three-quarters of a meter. The extreme horizontality supports the representation of the night convoy on its travels. Ermisch rearranged the motifs, selected excerpts where applicable and determined the typography and placement of text; eleven sentences suffice to provide the required information for the expressive series of pictures. Because the report is fictitious, photos are not used in the adaptation.

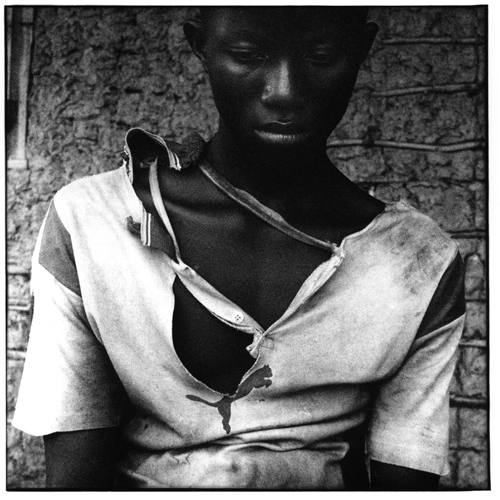

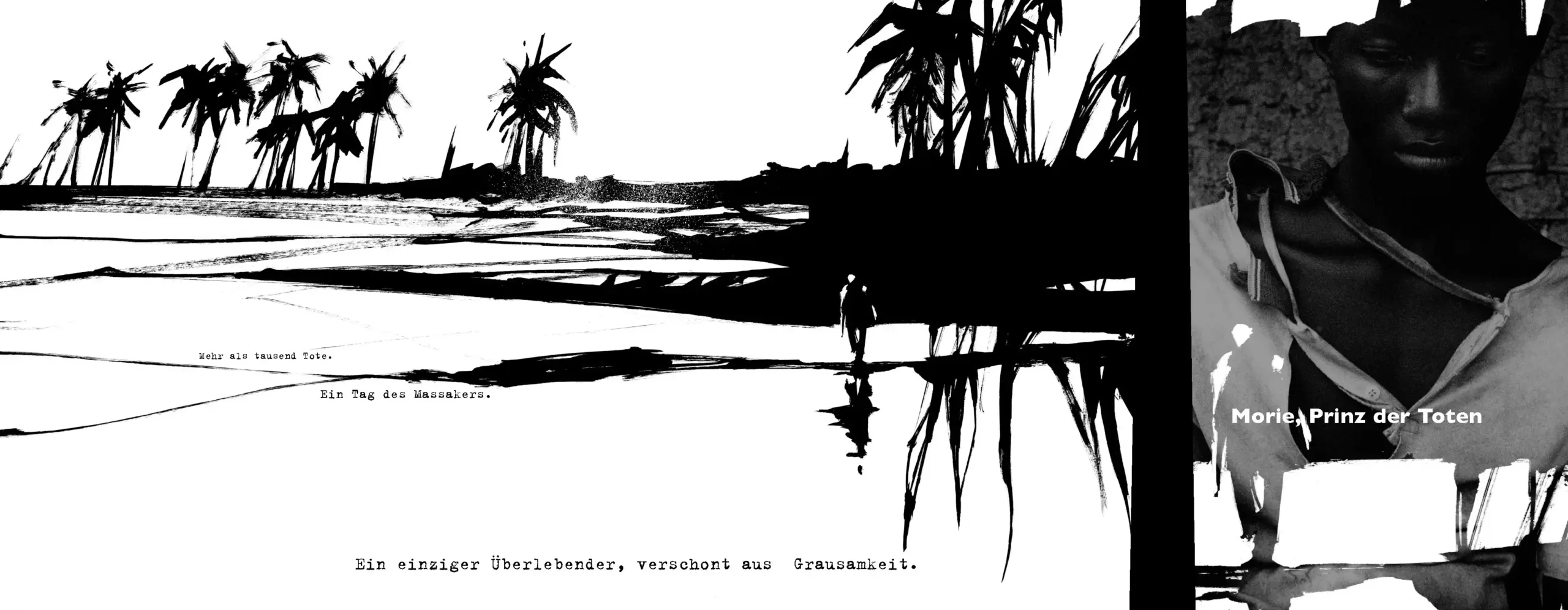

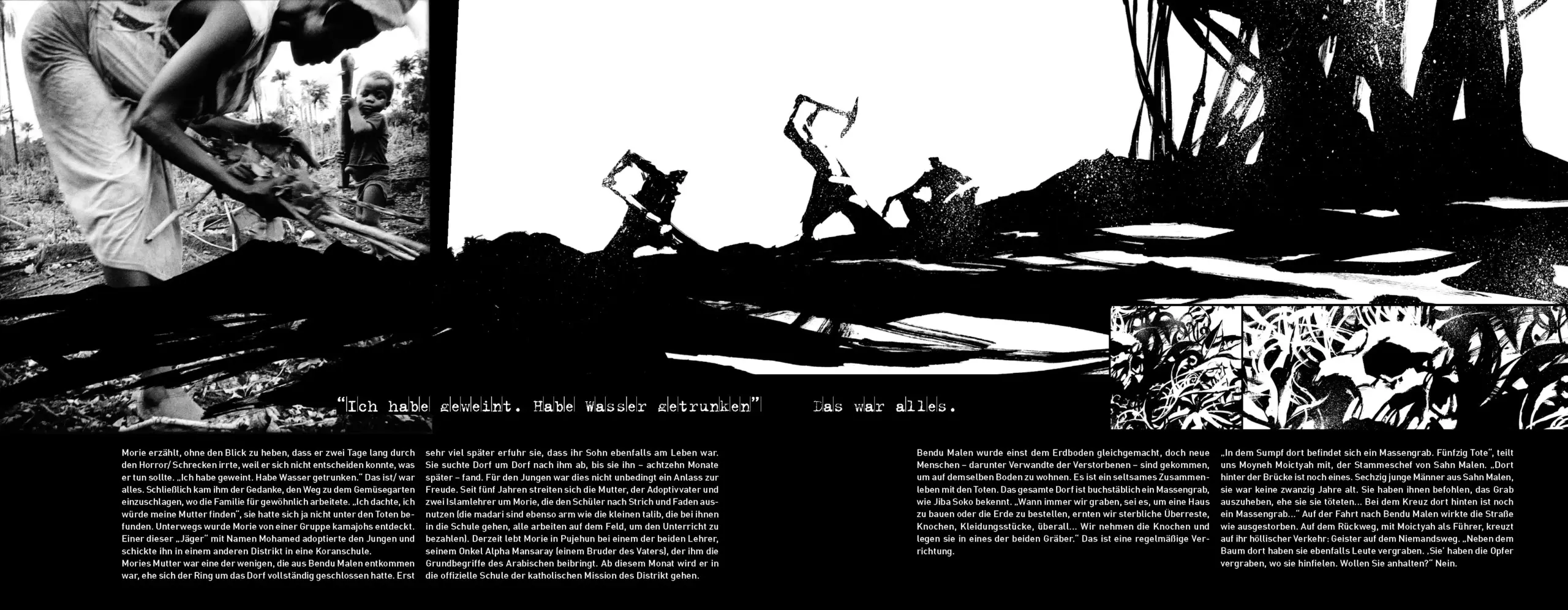

Things are completely different for Zezelj’s selection, the story of “Morie, Prince of the Dead.” For this piece, Ermisch not only used a number of long text passages from Mendes’s fundamental reportage, he also combined the illustrations with several of Böwig’s photographs. In 2003, the Portuguese reporter and the German photographer visited the town of Bendu Malen in Sierra Leone, the site of a 1977 massacre of villagers at the hands of attackers who have yet to be identified. Morie, who was five at the time, remains as the only surviving eyewitness. When Mendes found him six years later under the care of an uncle in the city of Pujehan, the boy remembered why the killers spared his life. “They showed me the dead people and made me the village chief, but they threatened to kill me if I ever crossed their paths again.”

Zezelj opted for a scraggy, black-and-white optical theme. Ermisch reduced the color saturation until the black areas appeared to be bleached out. Mendes’s extensive report was reduced even more drastically for the layout. Individual images shot by Böwig compliment what ?e?elj omitted from the sequences of austerely composed illustrations: The skulls from the mass graves and Morie’s cheerless eyes.

The third completed story was drawn by David von Bassewitz. When the German illustrator saw how his first drafts were dealt with, he started again from scratch. For “Peanut Butter,” who in 2004 was the last mercenary leader loyal to the deposed Taylor, von Bassewitz penned a confused web of lines from which the protagonists come undone. He also integrated a sequence of images resembling children’s scribbles. This sequence focuses on one of the worst aspects of the story, which is clarified by the book. The conclusion of the graphic illustrations is followed by one of Böwig’s photos. At first glance, it looks like a group of laughing youths. Then one notices the assault rifles in their hands.

As a story, “Peanut Butter” emphasizes the exemplary combination of the narrative elements in Black.Light. This project is attempting something new and remains in flux. Instead of a book, bound pamphlets may be produced as inserts for a newspaper so they might be distributed among the people. There is one thing the four initiators know for sure: Whatever Black.Light becomes, it cannot remain a solitaire – a gemstone in a lone setting – because the project is all about moving death into the light.